When I

was five, I staged a suicide with some ketchup and a butter knife. My

mom made me wear a pair of underwear that “felt funny,” and already

versed in my outbursts over shoes, socks, turtlenecks, and panties, she

paid my tantrum no mind. So there I strategically laid on top of a

detached cabinet door in my bedroom, mindful of not staining the carpet.

I wanted recognition, not revenge.

“You’re going to ruin the wood!” she scolded with tire. “No,” I thought, that’s not what was supposed to happen. I only wanted to make her understand how shattering these feelings were for me. We cleaned up the mess but we never really talked about it. I was a very sensitive child, tangibly and otherwise, and this is one of the first times I remember believing that emotions, especially sadness, were not good.

“You’re going to ruin the wood!” she scolded with tire. “No,” I thought, that’s not what was supposed to happen. I only wanted to make her understand how shattering these feelings were for me. We cleaned up the mess but we never really talked about it. I was a very sensitive child, tangibly and otherwise, and this is one of the first times I remember believing that emotions, especially sadness, were not good.

Eventually

I grew out of the clothing sensitivity, but I became more susceptible

to emotional disturbance. At my seventh birthday party, all of the

neighborhood kids stood around the dining room table to watch me open

presents, dropping crumbs of cobbler out of their absent-minded mouths. I

was happy that their attention was divided. Quietly I thanked each

person for their gift and crunched the scraps of wrapping paper into a

trash bag, worrying that if I did this too loudly, I would wake them

from their daydreams that were saving me from the spotlight.

They smiled through their fruit punch lips as I peeled the metallic pink paper off the remaining rectangular box. Oh no. Oh God, no. Not this. Panic flooded my veins and tears started cutting down my red cheeks.

“But I don’t like Barbies!” I cried. That wasn’t true. I fucking loved Barbies. This was the exact Barbie I had asked for. I was butterflied and pinned underneath a magnifying glass, and I was about to be found out. I was weak. The kids teased me, of course, and my heavy reaction only gave them more ammunition. For months I felt so ashamed and embarrassed to be me, and my brain told me again: sad is bad.

“But I don’t like Barbies!” I cried. That wasn’t true. I fucking loved Barbies. This was the exact Barbie I had asked for. I was butterflied and pinned underneath a magnifying glass, and I was about to be found out. I was weak. The kids teased me, of course, and my heavy reaction only gave them more ammunition. For months I felt so ashamed and embarrassed to be me, and my brain told me again: sad is bad.

A

few years later, I had no choice but to stifle my emotions — to be the

strong one. My mom married a troubled man; although, I begged her not

to. My grandparents had to forcefully take me away after their wedding

celebration because I was afraid to leave her alone with him. For the

next few years I had to be the eleven-year-old girl to pull a knife on a

grown man; the girl to bandage her mom’s wounds; the girl to hold her

while she cried. I had to be the girl to call the police. By the time

they showed up, my mom had already wiped her tears. Unfortunately, this

was something she had to learn the hard way. The first time the cops

were called and saw her crying, they agreed with my step dad that she

was “hysterical.” She had to hide her sadness to be taken seriously.

Eventually, they divorced. We didn’t really talk about it after that.

The horror was over, and we learned that things were easier when you

cleaned up your face and smiled. And I got good at it. And if I couldn’t

smile, I hid.

As

a teenager, I kept old pillows and shirts tucked away in my closets and

drawers. Whenever I reached a boiling point, I’d harbor in my bedroom

and press my face into the pillow, screaming as loud as I could. When

that wasn’t enough, I would rip the threads of the shirts and stab the

pillows with a knife. Sometimes I hit myself, throwing my fist towards

my face or, if no one was around to hear, I’d pry my tensed fingers open

and let my palm slap my wet cheek.

Mood

disorders have a tendency to show their onset as people stumble through

their mid 20s. And like clockwork, a few years after college is when I

began to cycle through the unpredictable waves of euphoria,

irritability, and depression. At first it started over something silly,

like breaking my Hollandaise sauce while making breakfast. Other times,

in utter rage of not being able to communicate my feelings, I’d throw my

cell phone across the room. Instances like this always had the same

outcome: me bawling, curled up in my closet or the smallest corner of

the kitchen, while my boyfriend stared in bewilderment. But those

depressions were short lived, and I’d explode into a stage of

productivity soon after. Within a two week period, I broke up with my

boyfriend who I lived with, quit my job, began the process of donating

my eggs, got an unconventional piercing, and started planning a tattoo

that would cover a quarter of my body. Being at this peak of my

exceptional self, I attracted a person who I thought I would spend my

life with. I had sunshine in my eyes and was the embodiment of joy and

what a human should be. I was flying higher than I ever had before; I

was manically in love.

We

were hardly apart for the next eight months, and I glowed and radiated

until I could no longer sustain it. As quickly as I ignited, I

smoldered. My breath sat like smoke over my rotting body for over a

year. “Where do you go” he asked, “when you sink into yourself like

that?” There’s always been a storm behind these sunny eyes, and now I

was stuck in the eye of it. Anytime I smiled, I could feel another piece

of me pulling at the reigns, like the moon dragging the sun back below

the horizon so darkness can take over once again. I couldn’t talk about

it. My whole life had been spent trying to camouflage my crazy.

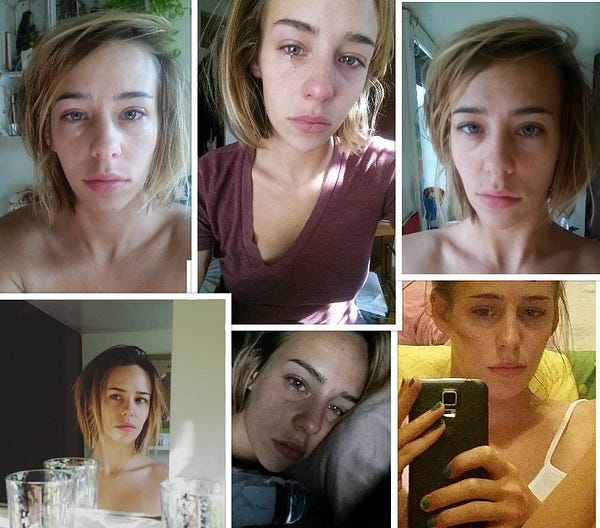

There’s

weight loss and weight gain and popped blood vessels from days of

crying. There are packs of Benadryl® being eaten to stay in the sweet

stillness of unconsciousness. There are moments of ferocity where you

hold your breath and tie pantyhose around your neck. There are broken

computers, smashed glasses and bloody knuckles. There are suicide

attempts and trips to the ER and stays in the psych ward. There are

hours and hours and hours of therapy.

There’s

cognitive impairment from the depression and the medication. Your brain

moves in slow motion, and you can’t remember when you last fed or

bathed yourself. There’s the art of mixing your perfect Rx cocktail, but

sometimes your meds don’t work. And sometimes they make your throat

constrict in painful throbs at night. Sometimes you have to alter the

dosage or change the medication all together. But it takes time for your

body to adjust, so all you can do is hold on for dear life and hope you

don’t hit turbulence until you reach your therapeutic level.

We

don’t talk about it because it’s the hardest thing to talk about.

People spend so much energy trying to keep the black holes in their

lives a secret, but now all of mine is spent trying to survive. When I

came out of the closet about being diagnosed with type II Bipolar

Disorder, an Internet troll mocked me: “my mental illness makes me special.”

Instantly he confirmed my lifelong fear — the fear of my feelings being

bad! I felt discredited and patronized. And, even worse, the fear of

people accusing me of seeking some sort of special treatment or pity. I

don’t want your pity. I want the respect of being listened to. I’ve put

too much time and money into self-care for you to doubt my diagnosis, or

worse, belittle it.

But

something else happened, too. People thanked me. They had questions and

stories and together we had strength. I helped a few people begin the

process of getting psychiatric service dogs. A few weeks later, I was an

active listener for someone across the country attempting suicide. My

relationship with my family improved. I think I showed them that they no

longer needed to sugar coat their feelings. If having a mood disorder

means learning how to love myself and build stronger relationships, then

I will happily shed my skin of shame and sanity. I will proudly wear my

badge of Bipolar Disorder. My name is Ashley, I’m mentally ill, and I

want to talk about it.

No comments:

Post a Comment